What About Whole-Class Novel Studies?

Join Our Community

Access this resource now. Get up to three resources every month for free.

Choose from thousands of articles, lessons, guides, videos, and printables.

What about having the whole class participate in reading a novel together? There are passionate opinions on both sides of the fence. Some feel strongly about the guaranteed exposure whole-class novels provide to classic and relevant works of literature. They are reluctant to give up the shared experience of common texts they believe have significance. They are also hesitant to relinquish books they see as rich with instructional possibilities.

What about having the whole class participate in reading a novel together? There are passionate opinions on both sides of the fence. Some feel strongly about the guaranteed exposure whole-class novels provide to classic and relevant works of literature. They are reluctant to give up the shared experience of common texts they believe have significance. They are also hesitant to relinquish books they see as rich with instructional possibilities.

Others believe that with the wide range of reading interests and reading levels in our classrooms, we can’t possibly select a book that is right for every student in the room. Pam Allyn (2011) argues that “being forced to follow in a book that is ill-fitting will not be a refuge or an inspiration, will not help them learn to read, and will not help them become a lifelong lover of text. Instead, it will alienate and isolate them from their peers" (para. 2).

Opponents of a whole-class novel approach also point to the amount of time it takes away from having students engaged in reading self-selected books written at their good-fit level. It can take four to six weeks to get through a novel as a class, and if any additional projects or assignments are added, that time frame is even longer. People opposed to this approach add that these lengthy, mandatory group studies kill reading motivation and enjoyment. (I must admit, I don’t have fond memories of either Lord of the Flies or Of Mice and Men from my high school days.)

Douglas Fisher and Gay Ivey (2007) agree that whole-class novel studies can be a detriment. They say, “Students are not reading more or better as a result of the whole-class novel. Instead, students are reading less and are less motivated, less engaged, and less likely to read in the future” (p. 495).

Kylene Beers (2016) says that based on the Coryell study, intensive study of a single book negatively affects reading attitudes. However, while opposed to whole-group novel studies where all children are expected to read a book in exactly the same way, she believes that in-common reading is important and that “we find community when we read books in common and we learn from one another.” Beers encourages us to provide opportunities to read the same book in different ways. She also reiterates the importance of choice.

Give kids a short list from which they can choose and then set a date by which the book must be read. Accept that some will race through it; some will need to sit with you to move through it together; some might need to hear parts read aloud. If you are thinking “But the kids won’t read it unless I’m forcing them through it,” then it’s the wrong book to read (para. 8).

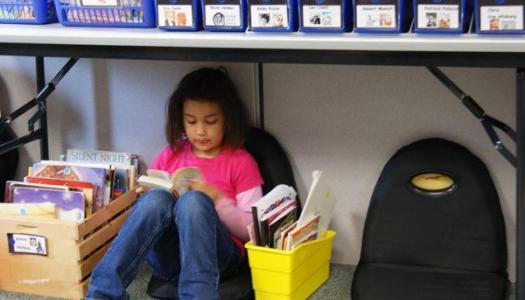

We stand on the shoulders of these and many other reading experts when we argue that students will be much more engaged, motivated, and interested if they are given extended periods of time to read independently chosen material. If there is a text we believe would benefit everyone, we use it as our read-aloud. Reading it to our students levels the playing field by making the text accessible to everyone. It also allows us to relish in the shared experience and language, as well as draw attention to instructional possibilities such as the author’s craft, themes, or relevant and interesting vocabulary.

This approach provides the opportunity for necessary, rich conversations around a book and gives the platform for important teaching opportunities without needlessly assigning the same text to everyone in the room. For instance, we might show students how an author uses foreshadowing in the read-aloud, and ask them to be on the alert for foreshadowing in their own good-fit books. Then when students are reading independently, we can facilitate one-on-one conferences around these lessons and topics to individualize, differentiate, and maximize student growth with texts chosen by each student.

Allyn (2011) sums it up well:

To read in school what one is driven to read, every day. To read at one’s own pace. To read driven by one’s own passions. To read on whatever device makes the most sense for that particular reader, whether it’s a mobile phone or an iPad. To invite all students to become, in essence, the curators of their own reading lives. This should be our reading program (para. 10).

Indeed, that should be our reading program.

References

Allyn, P. (2011, June 11). Against the whole-class novel. Education Week. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2011/06/15/35allyn_ep.h30.html

Beers, K. (2016). The whole-class novel: To read together or not? [Web log post].

Retrieved from http://kylenebeers.com/blog/2016/04/14/the-whole-class-novel-to-read-tog...

Fisher, D. & Ivey, G. (2007). Farewell to A Farewell to Arms: Deemphasizing the whole-class novel. Phi Delta Kappan, 88 (7), 494–497.

Retrieved from http://pdk.sagepub.com/content/88/7/494.extract