Allison Behne

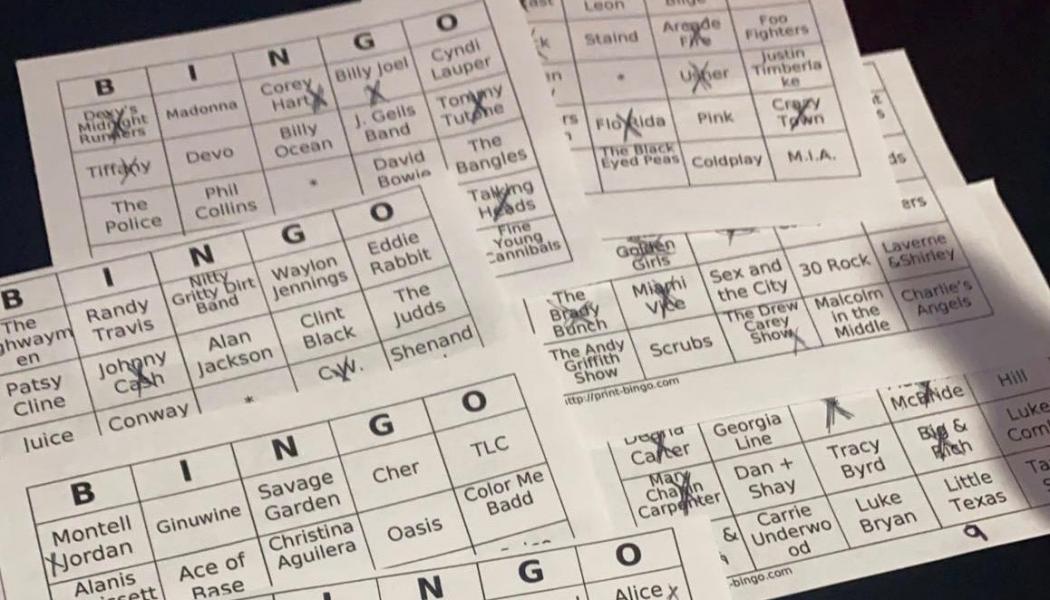

Have you ever played music bingo? A music genre is chosen, and grid cards with music artists’ names in each square—plus the infamous free space in the middle—are passed out to each player. The host then plays a song, and those who have the name of the song’s artist on their card mark the space. The first person to have a vertical, horizontal, or diagonal line of artists checked off wins. So fun!

When my husband and I joined the music bingo crowd at a local restaurant, we had a great time but quickly learned to appreciate the rapid search function on our cell phones—because even though we could sing almost every word to the songs, we could not think of the artist behind them. We were never the first to complete a bingo, but we had fun, because we could guess the artist and then confirm or correct our guesses based on the result of the search.

We live in a time when we have information at our fingertips. Want to know who made it through on American Idol? What the weather will be this coming weekend? What time the lunar eclipse is best viewed? Who sang what song in the 1980s? All we have to do is ask Alexa or do a Google search, and bam! the answer is right there. And, for questions like those we can usually rely on the first few results given. It really is convenient to have so much information so readily available.

But what about when the question is a little more in-depth and the response is not so black and white? What about when what’s at stake is more important than winning a bingo game? We can’t necessarily trust the first result of our search. We have to be responsible consumers of information and critically examine the source and feedback.

For example, any time we ask what “the best” of something is, we know the first results we get will most typically be paid advertisements or opinions—not extremely reliable. If we ask a question in support of or against something, we will most likely be flooded with opinion and one-sided information. And, if we search for information to help us in our teaching, the return will be a plethora of results that may or may not be accurate, from various sources that do not know our students and their needs. This is when it is up to us to use due diligence in studying the information we find. We find it helps us to ask a few questions when determining if something is worthy of our attention in the classroom.

- Who is the source? What is their background, and what are their credentials for providing the information they are sharing? Are they sponsored by anyone or do they work for a company with a conflict of interest?

- When was the information published?

- Who is the target audience? Is the information for elementary, middle, or high school teaching/learning?

- Are references cited, and if so, how many and where are they from?

Asking questions before forming a conclusion about what we find or are presented with is key. Vetting information isn’t something we should leave up to someone else. We must take on this task ourselves so that we know and trust we are doing what is best for our students.

News From The Daily CAFE

Commenting on Progress Reports . . . What Do I Say?

End-of-the-Year Routines for the Classroom Library

End-of-the-Year Writing Options